Candida Pagan is an M.F.A. candidate at the University of Iowa's Center for the Book. Earlier this year, she asked me to create a series of poems for a collaborative broadside project about the origin and evolution of heliocentricity (the discovery that the sun was at the center of the solar system.) The resulting series of prints, which were funded in part by a grant from the Caxton Club of Chicago, will be the focus of a reading this Saturday, April 4th at 2pm at RSVP in downtown Iowa City for Mission Creek Festival 2015, and will be displayed at RSVP until they are moved to the UICB. I sat down with Candida a few weeks ago to talk about the process.

[gallery link="none" size="large" type="rectangular" ids="21626,21621,21616,21613,21612,21608,21603,21605,21600"]

Lauren Haldeman: First I wanted to start by talking about the concept for the project. When you initially proposed the theme, I had a very basic notion of heliocentricity – I mean, basically I was born on this planet in this century and told that the sun was at the center of the solar system. I had a vague idea that at one point there was the indisputable belief that the earth was at the center of the galaxy (yes the entire GALAXY), and then that idea changed. But I really had no idea of the process of that change -- how that knowledge and belief system really evolved -- until you brought me on this project. So I was wondering where that interest came from for you?

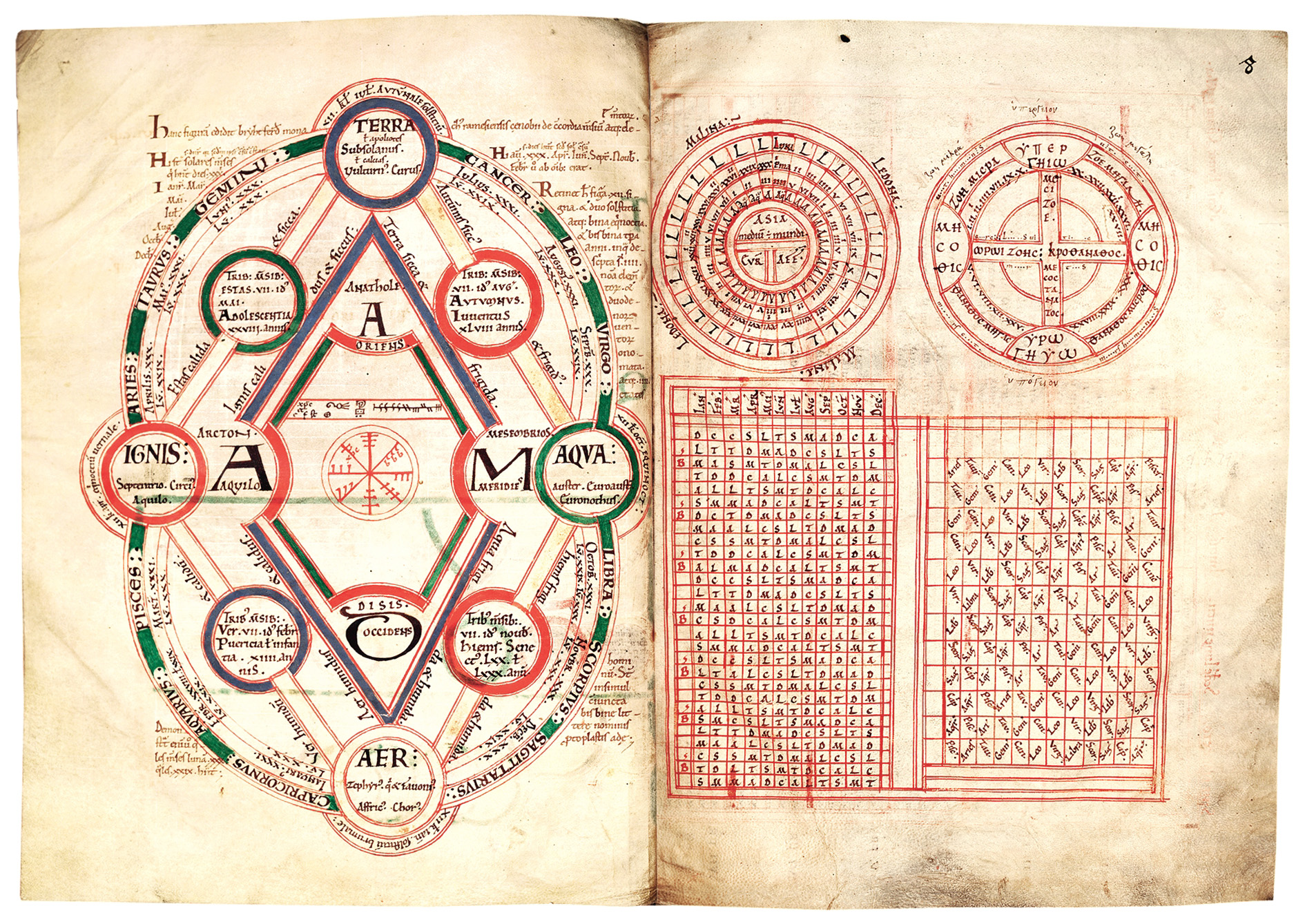

Candida Pagan: It started when I took a class on the Book in the Middle Ages. We were studying book history, and the evolution of the use of the book. I became really attached to this set of images in a book called Dunstan's Copybook. One image, “Byrthferth’s diagram," was this diamond shaped illustration with four corners and a figure eight going around the outside that had twelve spaces marked off to represent the zodiac. There were directionals, and it was all interconnected. I thought “What is going on? Why does this look like this?” So I became really interested in the world-view at that time. Why did they think that? What were they thinking? And that led me to geocentrism, the idea that the earth was at the center of the universe.

[caption id="attachment_21678" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Byrhtfer’s diagram[/caption]

Byrhtfer’s diagram[/caption]

LH: Right. Because that was a thing, for a long time.

CP: Especially in that it allowed an anthropocentric (human-centered) view of existence. Those elements of mysticism and what was accepted as absolute fact intrigued and surprised me.

LH: Right, that idea completely surprised me too – that every step of the way, these theories were accepted as absolute facts. Even the tiny, strange changes that were made – like that Saturn made a looping pattern in its orbit – those changes suddenly became absolutely HOW IT WAS.

CP: Yes. So to describe the evolution, we decided to make categories for your poems.

LH: Right.

CP: And these categories were based on people, let's call them investigators, who furthered information, who furthered knowledge in a significant way, and those people were speaking to different audiences. You can see that in the way they were writing. Kepler and Galileo for example– Kepler’s book Astronomia Nova, which cemented heliocentricism – it identified that planets go on elliptical paths and not spherical paths – that was written for a scientific audience; it was written for mathematicians. Galileo, on the other hand, was writing to a courtly audience (like, if you and I had a little more money.) His patrons were of the court.

LH: But still, each one of the investigators moved ahead the clarification of the theory…

CP: They were questioning “What is reality?” When Copernicus wrote his book, it was the first definitive heliocentric mathematical treatise. An anonymous person added an introduction to it that basically said “Just so you know, this isn’t really reality, this is all theory. This is hypothetical.”

LH: Yeah. Humans do not like change. Change takes so much time. I mean, this change in perception took multiple people’s lifetimes. Generations of people. You could live your entire life with a single version of “the universe” without any knowledge of what came before or after.

When I started the writing the poems, I was writing from the first investigator to the end, from Aristotle to Newton. With each poem, I started getting engulfed in that specific world view, I tried to really believe the idea at that moment. And it was hard not to believe – because language is so convincing. So every time that I moved forward in the evolution of the theory, it was a little epiphany. But the biggest one for me was Newton: how, when it had become entirely apparent that the earth was not the center of the universe, that meant that the earth is moving around something. And then all of a sudden there was this huge question: how does everything stay on the earth? Why aren't we just spinning off? They were basically set directly onto the path to gravity. I mean the change of perspective actually forced the investigation that led to the discovery of gravitational force.

CP: It becomes super important.

LH: (laughing) Right! It becomes super important!

CP: Its just incredible. Not only the capacity of humans to evolve in their way of thinking, but also our concept of reality could absolutely change tomorrow and we would figure out a way to work with it.

LH: There would be a lot of fear and there would be a lot of fight back...

CP: But we would figure it out. And I think at this point we KNOW that we don’t know…

LH: Thank goodness…

CP: But still, how much is there?

LH: I don’t know! Ok, let’s go from these enormous ideas to the actual physical process of making the broadsides. Let’s talk about letterpress, because that seems equally as fascinating to me.

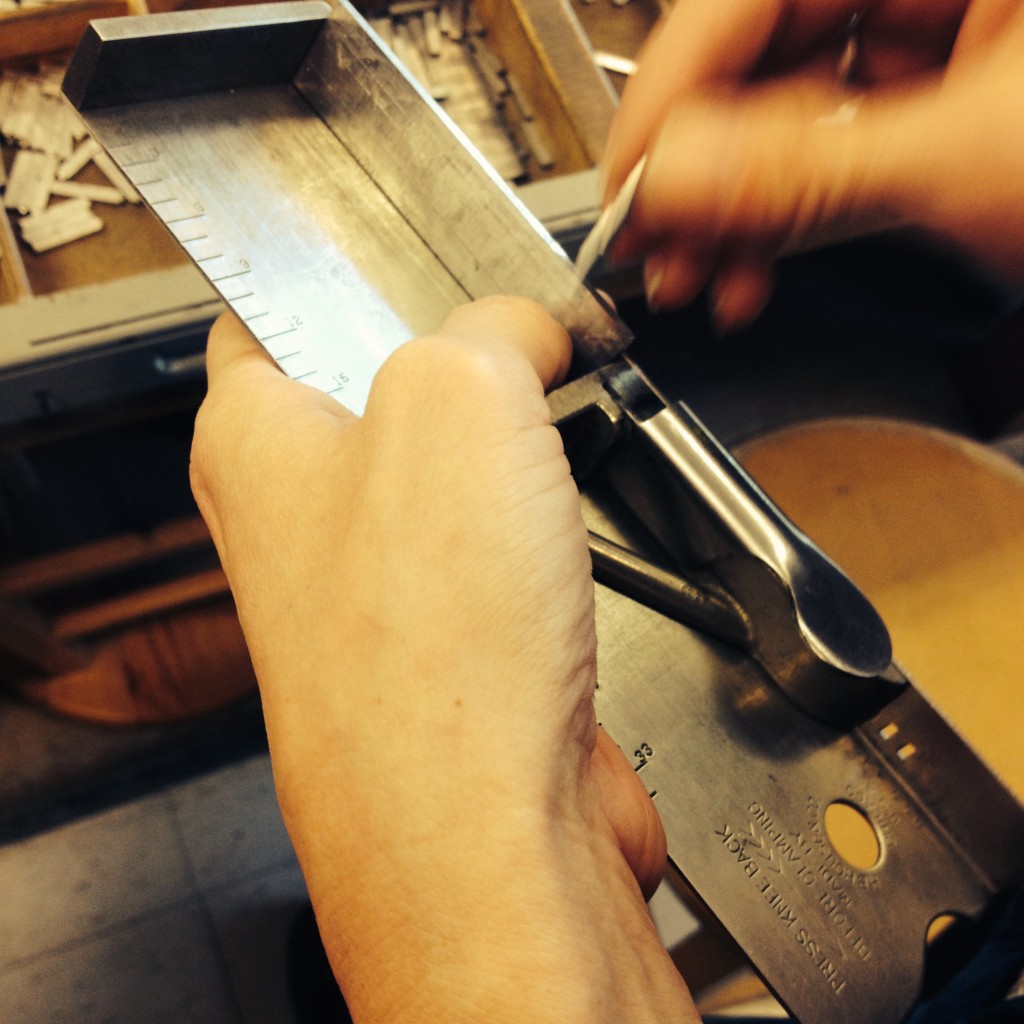

CP: Yes, let's see. So typesetting is this process in which the human hand becomes the typewriter. There’s a case that holds the letters in its own little pocket. And as you typeset, you read the poem letter by letter, space by space. You put those tiny letters in place. A ‘return’ on a keyboard is actually a piece of metal, a flat piece of metal, in typesetting. You choose a piece of leading – 1 point leading, 2 point leading, etc -- and you put that in. You are holding another piece of metal called a ‘composing stick’ and you write out the poem, piece by piece. You have to proof it to make sure that nothing is upside down or backwards: b’s and p’s for instance are easy to mix up. You are placing the letters upside-down in the composing stick, so it is a little confusing.

Then you run those through a proof press with carbon paper just to make sure you are doing everything correctly. And there are characters that are not alpha-numeric, like punctuation, asterisks, money signs and slashes. Slashes are not very plentiful.

LH: Yeah, and my poems had a lot of forward slashes in them.

CP: Yes! And so, at the Center for the Book, we’ve inherited the original type-lab’s type. We have a ton of metal type available to us as students. I went through almost every single drawer of type looking for your slashes…

LH: (laughing) That’s insane…

CP: In all of those cases, I could find maybe seven slashes that were uniform. So, I had enough for each poem, but only one poem at a time. So while I was setting the poems I found out that a slash takes up the same amount of space as what is known as a '3/M' space.

LH: Why is it called a ‘3/M’?

CP: The capitol letter ‘M’ is essentially a little square. Let’s say you have 12pt type. An ‘M quad’ is a little space of lead that won’t print. If you divide that ‘M quad’ into three, each section would be called a ‘3/M’. If you divide it into four, each one would be called a ‘4/M’.

LH: So it is skinnier the higher the number gets.

CP: Yes. So I would just put a little extra ‘3M’ space in the other poems for where the slashes were supposed to go, and then I would swap them out.

LH: I would never have thought to worry about those slashes. But if we were in a typesetting era, someone surely would have said “You are using quite a bit of slashes there, my friend. You need to cut back on these slashes!” Apparently in, like, an Irish accent.

CP: Right ... but it was part of the poetic form! And you were making a formal reference.

LH: I was trying to use the Ghazal form to shape the work. I started off with that as my base form. But then it began to depreciate.

OK, one last question about the artwork on the broadsides: I watched you press the type, but I didn’t see you make the art. What was the process?

CP: Letterpress is basically typeset or polymer plates that are printed on a relief press. So it is relief printing. The ink touches the top of the letters and the letters are pressed into the paper. I also printed the images in relief.

LH: How did you make the reliefs?

CP: They are foam plates.

LH: What? You cut those out? You cut those circles out?

CP: I cut those circles out.

LH: (laughing) That’s sick. You have a problem.

CP: (laughing)

LH: What with like an Exacto knife…?

CP: With scissors… (laughing)

LH: Candida! I thought for sure you used some sort of machine to make those. Did that just take forever?

CP: Copernicus took 75 years, right? And I took about five hours to print each image.

------------------

Lauren Haldeman's poems appear in the series 'The Eccentricity is Zero'. She is the author of the collection of poetry Calenday (Rescue Press, 2014). Find her on twitter @laurenhaldeman

Candida Pagan is an M.F.A. student at the University of Iowa Center for the Book. She publishes collaborative fine press chapbooks and broadsides under the imprint Digraph Press and makes artwork on paper...unless it's on something else. Other Digraph Press titles include Make This Happen or Pass Away, by CS Ward and The Ship, by Stephen Sturgeon. Find more of her work on tumblr: http://candidaetc.tumblr.com