I didn't grow up in a house with shrines, at least not purposefully intended shrines. When I was a child, it wasn't necessarily part of my family's religious or cultural traditions, and it tended to be thought of as "other." When I moved to Iowa in my early twenties though, I was hanging out with writers, puppeteers, musicians and artists who all shared in the same strange (and unspoken) midwest ethic that declares a deep connection between the act of "making" (and I mean any form of "making": art, woodworking, literature, farming, crafts, music, knitting -- you name it -- ) and spirituality. Woven into this, too, was a strong sense of home, a pride in the DIY approach and a very personal working notion of tribute.

And I started to notice an interesting thing my friends' homes: shrines.

Mallory, for instance, had a single shrine dedicated to all of her remembered ones, in the entryway of her farmhouse outside of West Liberty, IA. It was decorated with calaca skeletons from Mexico, tall votive candles of saints and various dried plants. It was well maintained, always included in conversation, and full of light and offerings and scent and smoke.

E.J.'s shrine, also in the entry way, was decorated with mirrors and tiny ornamental circular pictures, honoring both her human and her animal friends.

Another friend had outdoor shrines, concrete and glass, with lights hung from branches.

None of the shrines I encountered were "traditional" in any religious sense: they were all fiercely individual and multi-thematic, according to the preferences of each person who maintained it. I liked this.

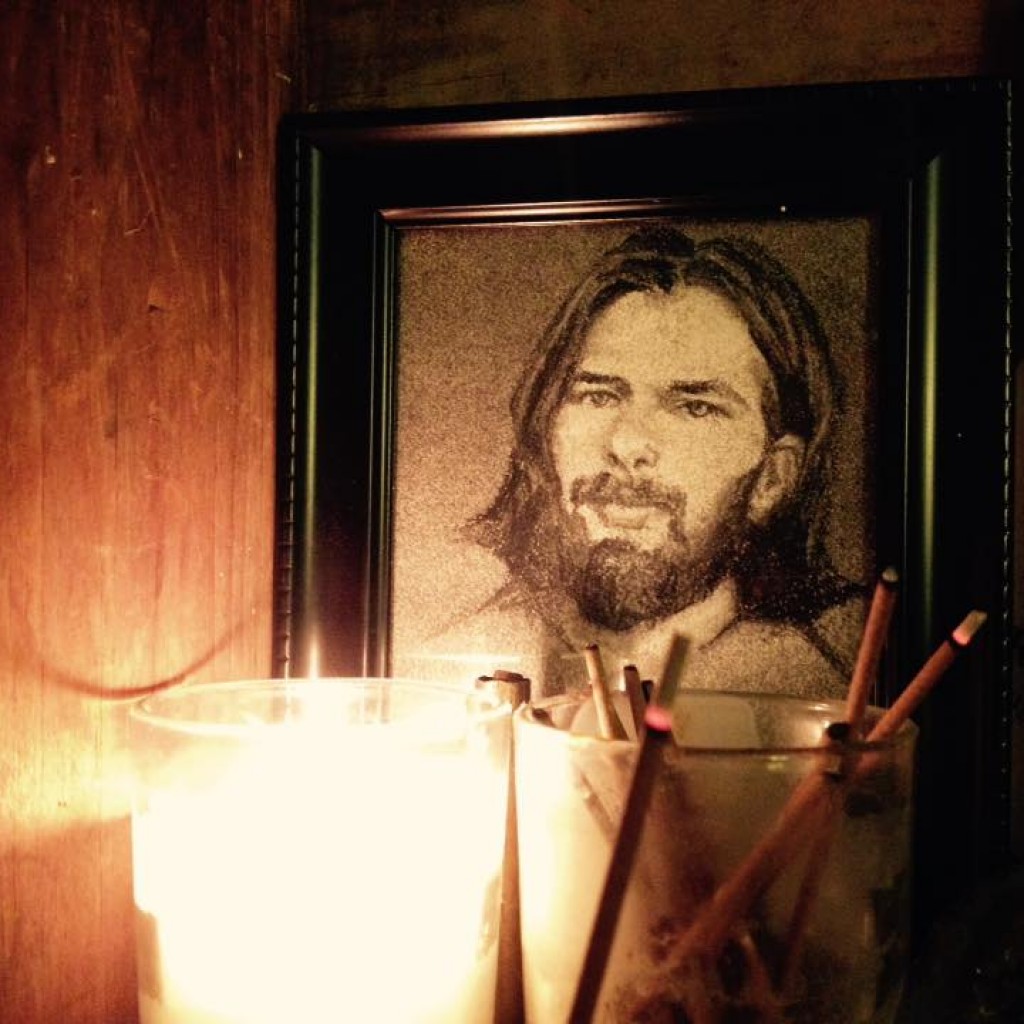

When my own brother, Ryan, died on November 2, 2012, I took to making him a shrine almost immediately and without even thinking: I wanted a place to visit him daily, and I wanted him to be a part of our home and family.

At first, I just started one on top of a bookshelf, a temporary make-shift area. A few weeks later, Ben and I found an old wooden box at a local thrift store, and hung the box on the wall as a shrine chamber. We started simply, adding a single photo of him and a candle. Over time, though, things started to gather: feathers, stones, more pictures, candles, drawings, a wacky ying-yang stress ball, a geode. The objects call out to be included. In this way, it is very much a distinct tribute to Ryan, who was also a collector of the small and forgotten items of the world. Everything had meaning to him.

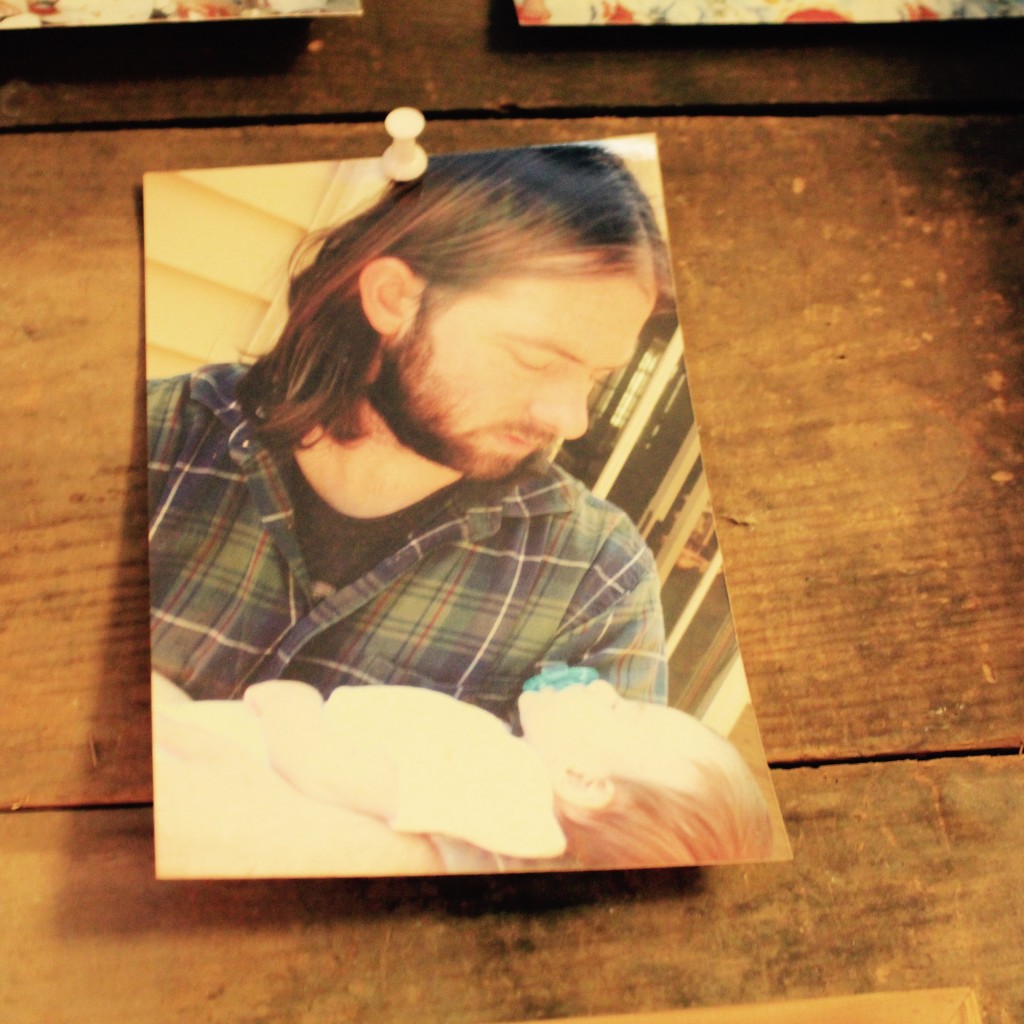

My daughter was only 2 years old when my brother died. She will not remember ever knowing him, not as a living human being, at least. But I fervently want him to be a part of her life. He dedicated his life to working with young children as a early childhood educator; he taught kids in Denver as well as in impoverished schools in Brazil. He had a special gift for being able to connect and understand the world of the child. He believed in kids.

So every week, my daughter and I "greet" Ryan at the shrine. We say "Hi Ryan!" and light a candle. We talk about him: what he was like, what he did. At the end, we have a special tradition. There is a picture in the middle of the shrine. It is a photo of Ryan holding Ellie, when she was just three months old. He gazes down at her and it is just love. My daughter and I look at that picture, and after a second or so, I ask her "Who is that?" pointing at Ryan. She says "Uncle Ryan." Then I say "And who is that?" pointing at the tiny baby in his arms. "Me" she says.

And we leave it at that. That's all there needs to be.

SHRINES BY FRIENDS

[gallery type="thumbnails" ids="22077,22073,22079,22072,22076,22075,22074,22078"]